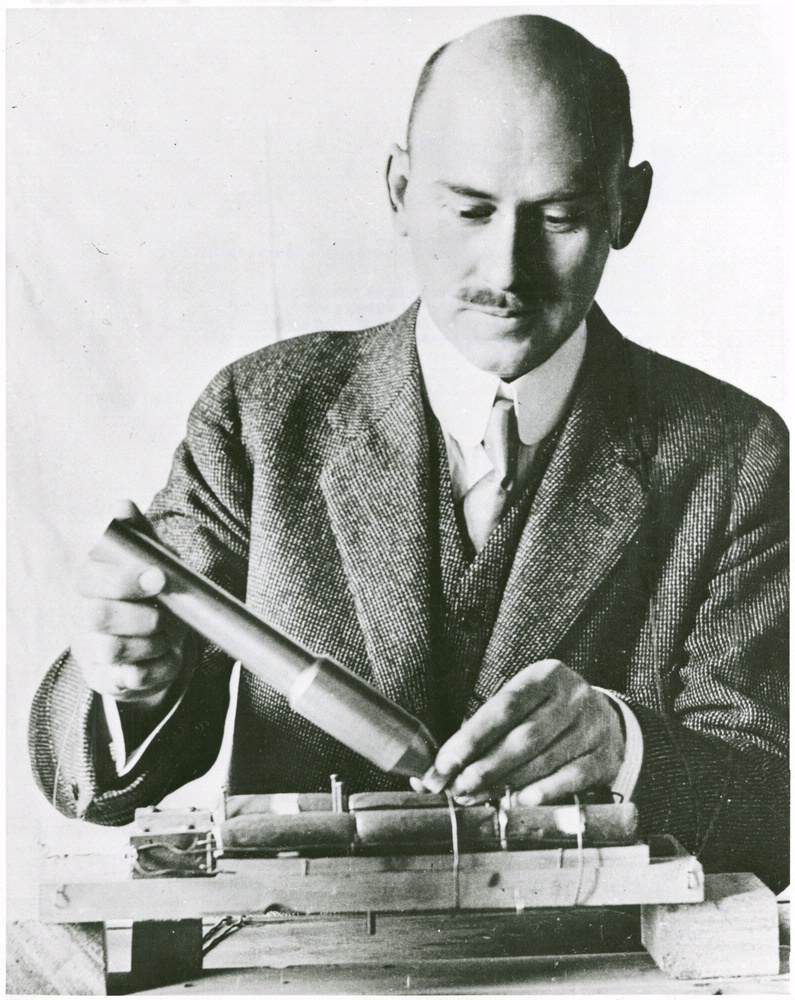

After years of investigation, Goddard realized in 1909 that the rocket was indeed the propulsion system for spaceflight. A talented physics student, he quickly worked out the equations. He knew nothing of parallel work then going on in Europe.

In 1916 he applied for a grant from the Smithsonian Institution. Charles G. Abbot, director of its Astrophysical Observatory, was excited by the possibility of launching instruments a hundred miles high with a rocket. In 1917 the Smithsonian granted Goddard the substantial sum of $5,000.

Within two weeks the news spread around the world. The press sensationalized Goddard’s proposal. But space travel in science fiction and the media quickly changed. Thanks to Goddard, the rocket was clearly seen as the way to get into space.

Lindbergh brought the rocketeer’s work to the attention of pilot and philanthropist Harry F. Guggenheim. In 1930 Daniel Guggenheim granted Goddard $50,000. Goddard decided to move to Roswell, New Mexico, where the dry, warm climate would allow experiments year round.

Why Roswell, New Mexico? It had three features someone testing rockets would find attractive: wide open spaces, few people, and good year-round weather. Goddard’s wife Esther said Roswell was a place “where we would not bother anyone and no one would bother us.”

In 1942 the Navy moved him and his group to Annapolis, Maryland, not far from the Naval Academy. He experimented there on liquid-fuel motors during World War II.

Goddard refused to work with other groups and used only a small crew of assistants. As a result, he had little technological influence on American rocketry.

But he left another legacy. A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes fundamentally altered the world’s perception of the rocket and of the feasibility of spaceflight.

“It is difficult to say what is impossible, for the dream of yesterday is the hope of today and the reality of tomorrow.”

— Robert Goddard